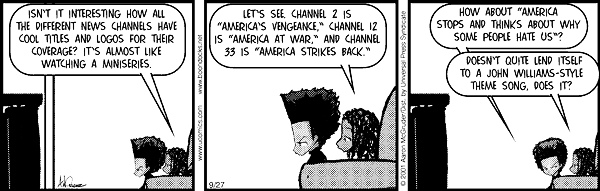

When people ask me why I’m interested in going to Afghanistan, I always have a hard time answering because my gut response is ‘Why aren’t YOU?’ On September 11th I was at boarding school in Putney, Vermont and I remember reading this Boondocks comic that seemed to express what I was thinking.

My reaction to September 11th was an introspective one, I asked myself ‘Why do people hate us so much?’ and ‘Why didn’t we know before?’, ‘What have we done?’ and ‘What can we do to make sure these people don’t attack us anymore?’

A few years after the attacks I was a Junior in high school and I had the opportunity to meet a group of women judges from Kabul. Just learning that there were women who had been judges in Afghanistan complicated my view of Afghanistan. Actually meeting and spending time with them made me more and more curious about the people there and what they were doing. If there were women there going to work every day there must have been at least two buildings standing, their homes, and their workplaces; all I saw on TV was burning rubble. I became really interested in the people and the culture, what was sharia law? What was really the situation there? (Here’s a great video/interview I just found about everyday life in Afghanistan if you’re as curious as I was.)

I studied Afghanistan in college as a Near Eastern Studies major at the University of Chicago. I learned Persian and Pashto. I decided to double major in Geography because I kept finding that the problems in Afghanistan had to do with ethnicities isolated by geography. The colonialist boundaries had put two very different ethnic tribes together in one country (along with many other tribes and ethnicities, Afghanistan is extremely diverse, many people thought I was an Iranian-African from the Bandar-Abbas region). I wrote my thesis on how the legal systems in Afghanistan were distributed geographically.

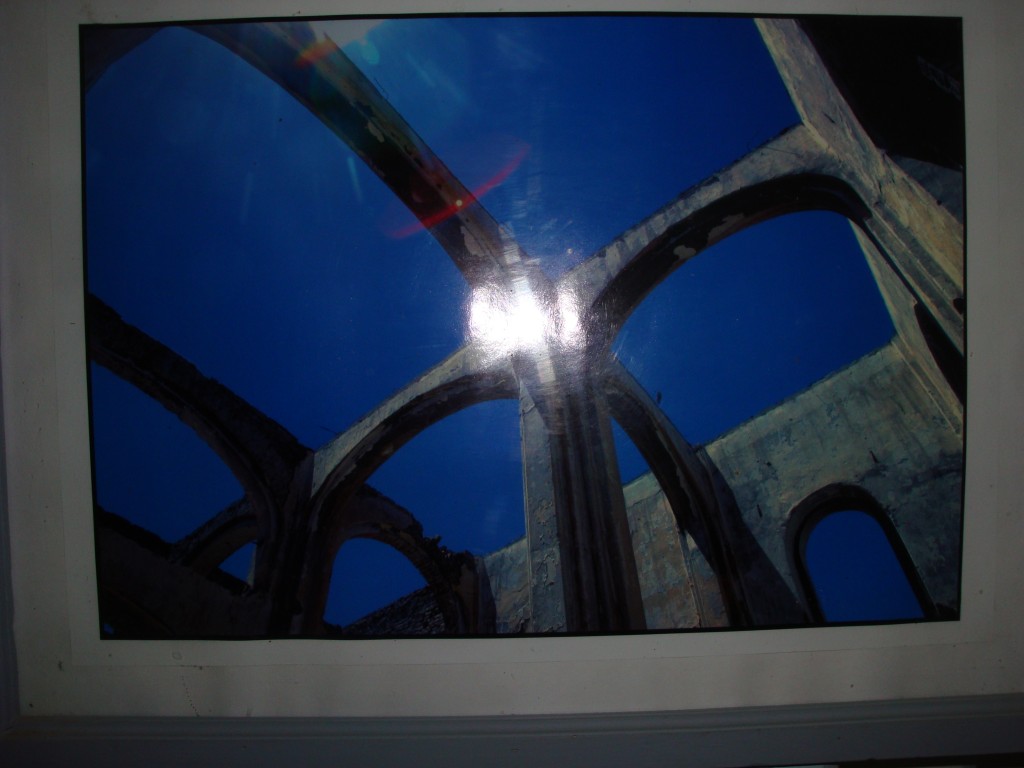

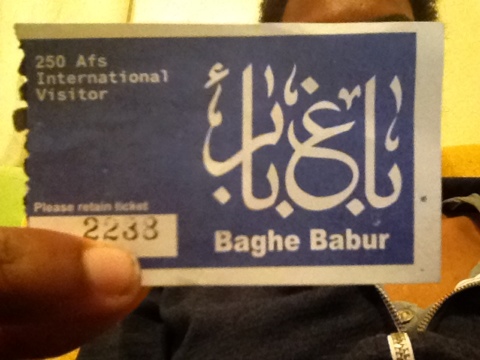

As you know, a few months ago I went to Kabul. In Kabul I heard 3 things with surprising consistency, the biggest problem or challenge in the country was lack of security, everyone thought the Pakistani government was to blame for many of the country’s problems (that the US should stop funding Pakistan) and everyone we asked wanted to keep US or international involvement in some respect. We talked mostly to middle-class urbanites in Kabul, but this was the anecdotal evidence we were able to gather. You can see the evidence of 30 years of war in and around Kabul, in every neighborhood our tour guide pointed out a building that had a suicide bomb attack, the palace and museum were destroyed, we went through check-points almost every day. But I can’t imagine what it’s like in the countryside.

We did have a couple different points of view to complicate this. One was on the second day at a refugee camp, which I talked about in an earlier post. The other was in the village of Istalif at a small traditional restaurant. We were served a dish called chainaki (lamb stew served in ‘china’ – tea kettles) as we sat on the rugs. A few different men came in and out of the restaurant and we were able to chat with them informally, one of the few times we weren’t on a scheduled meeting.

First we talked to the older man who we called Kaka meaning uncle, a term of respect and endearment. He talked about life in his village over the years. He and his family did pottery and leatherwork before the revolution, and the bazaars were much bigger. He lost his business after the revolution and the village of Istalif lost 75% of their population. Most of the money from Istalif went to Kabul, but there were a few families who came back and are doing agriculture again (wheat, fruit, figs, apricots, apples and cherries).

There was also a young man who was up for the weekend, he runs a camera shop in Kabul. We talked to him and his friend for a bit. He said some Afghans thought the Qur’an burning was done by Brits and not the US. He talked to us a little about what Islam meant to him, and how if everyone followed the Good Book we would have no problems. They brought up some issues about Afghans who can’t get Visas to the US. They said if the US is really an ally they should let Afghans travel to the US on business. If we stay in the country, we stay as an ally, but he warned, if we stay and try to start a war that history will teach us what happens to people who try to take over Afghanistan. Persians, Indians, British, Russians, no one has ever held Afghanistan.

The more research I did about Afghanistan the more confused I was about US involvement. I wrote a thesis, studied the geography, learned the culture and even went to Afghanistan. If I had to characterize the Afghan people, based on my experience, I would say they are generous, resilient and hugely diverse. I essentially came to the conclusion that I can’t figure out why Afghans bombed us because Afghans didn’t bomb us, some crazy terrorists did, they happened to live in Afghanistan (well, Pakistan). I recently heard this statistic about how Islamic people are more likely to be the victims of terrorist attacks than the perpetrators. Fear cannot be the driving force in this debate, we must come from a place of diplomacy and compassion, not imperialistic hubris. But I still can’t tell whether it’s right to stay in the country, helping people as well as killing people, or to leave, abandoning them altogether.